Jack’s Speech commemorating the

1983 marine Beirut barracks bombing

“Beirut is not hell, but you can see it from here.”

– U.S. Marines in Lebanon

– U.S. Marines in Lebanon

On Sunday, October 22nd, 2023, Jack addressed a gathering of the Beirut Veterans of America in Jacksonville, North Carolina at the VFW outside the gates of Marine Corps Base Camp Lejeune on the eve of the 40th anniversary of the 1983 Marine Beirut Barracks Bombing, an attack that claimed the lives of 220 Marines, 18 sailors and three soldiers. His remarks are transcribed below.

Jack’s keynote speech: Beirut veterans of America

Good evening.

It’s an honor and a privilege to join you this evening — to look out upon this gathering of esteemed Beirut veterans, their brothers and sisters, wives, children, grandchildren and even a few great grandchildren.

It is wonderful, too, that we have with us veterans and families of the Italian and British forces who worked with you in Lebanon.

I spent two decades in the SEAL Teams, fighting in the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. Even though our service is separated by geography and time, we are, in all actuality, veterans of the same fight — America’s war against terrorism.

That war, started in Beirut.

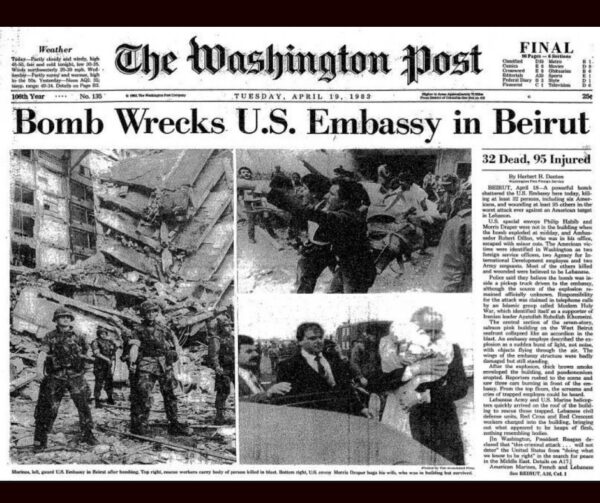

It began at 12:05 p.m. on April 18, 1983, when a Shiite terrorist rammed his GMC pickup truck loaded with the equivalent of 2,000 pounds of TNT into the American Embassy. The subsequent explosion collapsed the front of the eight-story chancellery, killing 63 people, including 17 Americans.

But that attack — which we now know was the opening salvo in a new war was a precursor to the horror that would follow just 188 days later – a horror that would be visited upon many of you.

Lebanon at that time was torn by eight years of civil war, an ancient religious conflict that pitted Christians against the Sunnis, Shias, and the Druze. That war had killed tens of thousands and devastated the once-beautiful capital of Lebanon, formerly hailed as the “Paris of the Middle East.”

Foreign actors seized on this conflict. Israel, Syria, the Soviets, and, of course, Iran — whose penchant for violence and destruction continues to this day.

Into this volatile mix, President Ronald Reagan sent you — the United States Marines. You were joined on the beach by American sailors and soldiers — all part of a multinational force made up of troops from Italy, France, and England. You went, not as combatants, but on a mission of peace, guided by the famous passage from Matthew, Chapter 5, Verse 9 — words that Major General Al Gray had painted on a plaque that hung in the officers’ club. “Blessed are the Peacemakers, for they shall be called the children of God.”

On that mission, you conducted patrols and passed out candy to children. Drs. Jim Ware and Gil Bigelow visited an orphanage to perform dental work. Others among you built playground equipment for impoverished villagers. There was an optimism, a faith in the value of the mission. “We may or may not be successful,” Lieutenant Don Woollet wrote home. “But the undertaking, the quest itself, is noble. No other nation but the U.S. would ever attempt it.”

But that summer, the landscape changed.

The warring and tribal politics of Lebanon re-emerged.

The distant battles, which lit up the mountains at night, found you at the Beirut airport. In late August, George Losey and Alex Ortega were killed in a mortar strike. Their deaths were followed days later by the loss of Pedro Valle and Randy Clark. More than a dozen others were wounded.

Back in Washington, Reagan’s advisors battled one another while Congress fought with the White House over the War Powers Resolution.

The end result was a political paralysis that left you in harm’s way.

It was a situation aptly described by Congressman John Murtha: “We have put these Marines,” he declared, “in an impossible situation.”

And he was right.

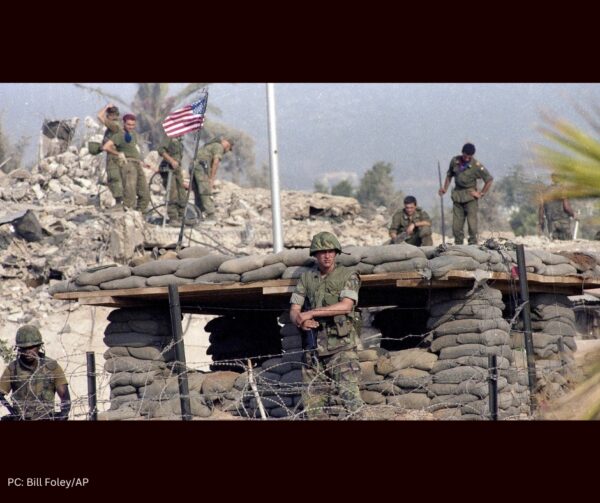

Caught amid an escalating civil war, you had few options other than to fill sandbags — 100,000 in just the month of September — and hunker down in bunkers as rockets and mortars rained down. “I can honestly say,” Sergeant Michael Massman wrote his family, “that I know what the human heart tastes like, because mine has been up in my throat quite a few times.”

Beyond the bunkers and the sandbags, your safety depended upon the perception of America’s neutrality in a factional civil war. “If that should ever be lost,” Major George Converse wrote his wife, “then we’ll become targets.”

But key players in Washington failed to appreciate that reality.

Under immense pressure from White House emissaries — hoping to use the Marines and the Navy to apply political pressure on Syria — America intervened on behalf of the Lebanese military in the fight for Suk al-Gharb.

And with that action, the Rubicon had been crossed.

“My gut instinct,” Colonel Geraghty leveled with his staff at the time, “tells me the Corps is going to pay in blood for this decision.”

There was a momentary lull with the September 26 ceasefire, though as Geraghty rightly observed: “Ceasefire is a relative term in Lebanon.”

For a few days you experienced relative calm and tranquility, which was accentuated by the fact that the deployment was winding down. Home, which had seemed so distant under the thunder of artillery, once again came into sharper focus. “People are starting to sing in the showers — a first for Beirut,” Dr. John Hudson wrote in a letter to his wife. “Everyone, including yours truly, is getting more and more excited about going home.”

But that peace proved elusive.

Gunfire erupted across the capital.

Day by day, the attacks escalated.

Snipers began to target you, claiming the life of Allen Soifert on October 14th followed two days later by Captain Michael Ohler.

In Washington, a handful of voices warned of a brewing catastrophe, including Congressman Larry Hopkins, who visited Beirut in September. “I don’t want this country,” he told the press, “going into the body bag business.”

Representative Sam Stratton agreed, warning Defense Secretary Caspar Weinberger: “You’re going to have a massacre on your hands.”

But the administration was slow to move. And Iranian-backed Shiite terrorists seized that moment.

The horror came shortly past daybreak on the morning of October 23rd, 1983. Inside the Battalion Landing Team Building, 350 men slumbered. It was Sunday. A day of rest, which normally included a little football and an afternoon cookout.

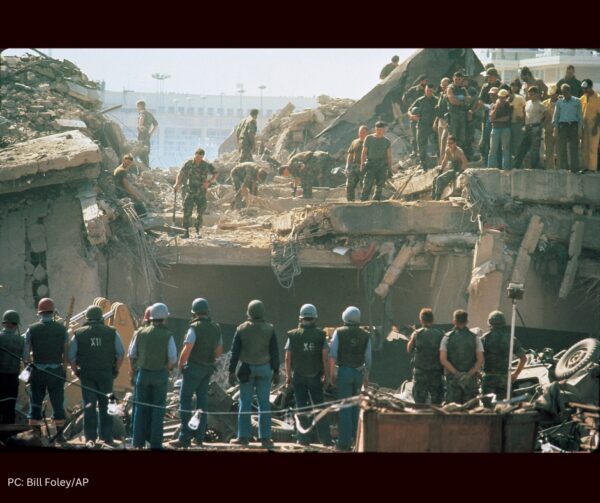

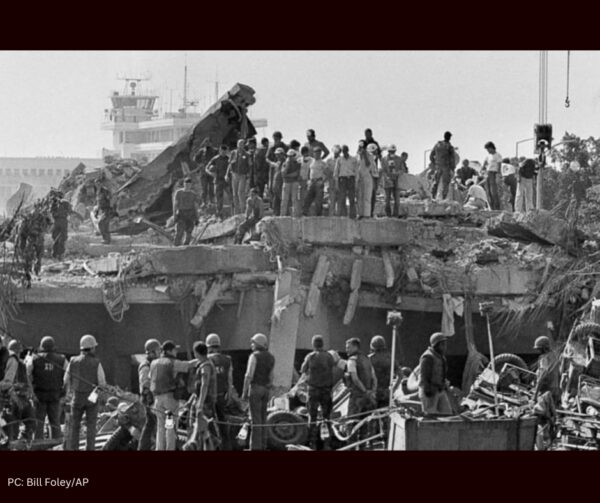

A Mercedes stake-bed truck would shatter that calm with a 6:21 a.m. terrorist attack. The ensuing blast, which rivaled as much as 20,000 pounds of TNT, proved the largest nonnuclear explosion FBI investigators had ever seen.

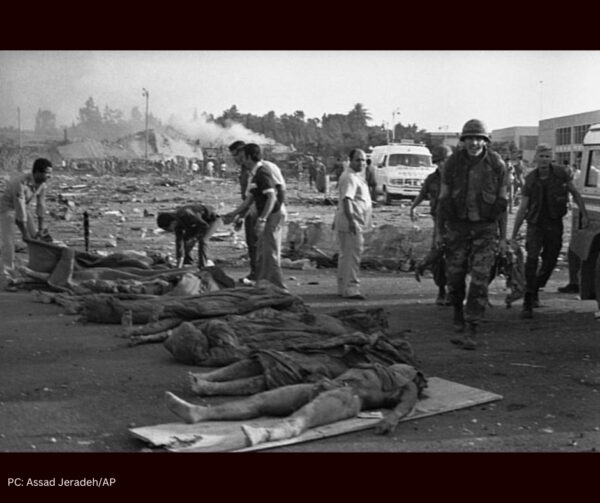

The blast would claim the lives of 220 Marines, 18 sailors, and 3 soldiers. Another 112 were wounded, including some of you in this room tonight. A near-simultaneous attack a few miles north killed 58 French paratroopers.

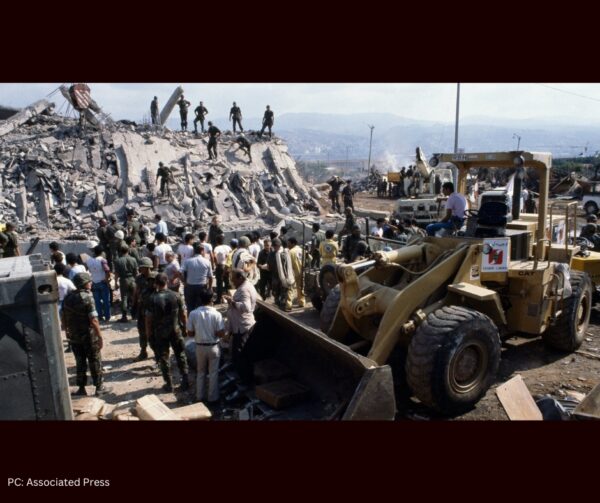

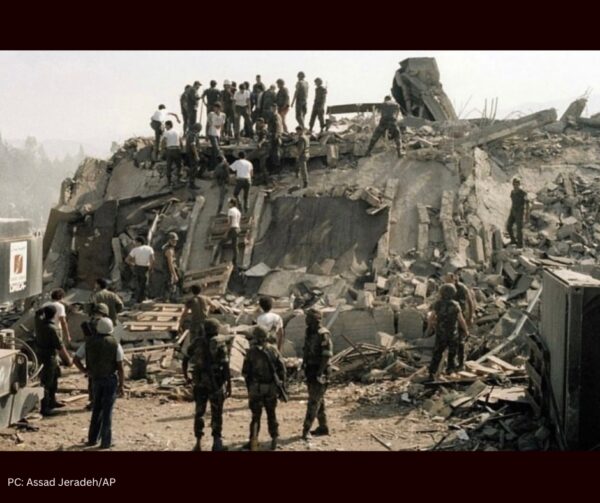

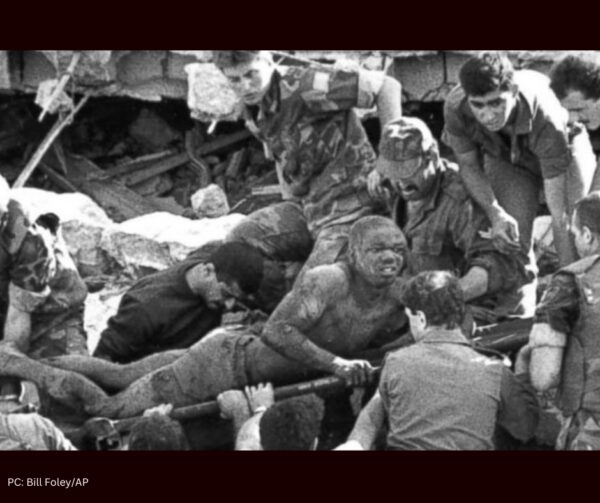

What followed this tragedy was one of the greatest rescue stories in modern history. Tossed from your racks, you immediately sprang into action, attacking the rubble pile with shovels, Ka-Bars, and your bare hands, shredding fingers and fingernails as you dug through the crushed concrete and tangled rebar in search of friends entombed inside the wreckage.

With the medical department largely wiped out, dentists Jim Ware and Gil Bigelow led medical efforts. Father George Pucciarelli and Rabbi Arnold Resnicoff administered last rites. Many more of you hauled stretchers, guarded the perimeter, and held the hands of the wounded and comforted friends.

The attack that morning signaled the end of America’s involvement in Lebanon, though it would take a few more months before the president would move the Marines back aboard ship and eventually bring you home.

For many of you, the physical scars of that attack would forever tattoo your skin and brand your souls. Lt. Colonel Larry Gerlach, blown out of the second floor of the BLT, would be bound to a wheelchair.

Corpsman Don Howell, buried in the basement of the collapsed building, remains today blind in his right eye.

And Lisa Hudson — like so many other widows — would be left to raise her son alone. And then there are the children, like Will Hudson, who spoke so powerfully to you at the 30th reunion, who would grow up without a father.

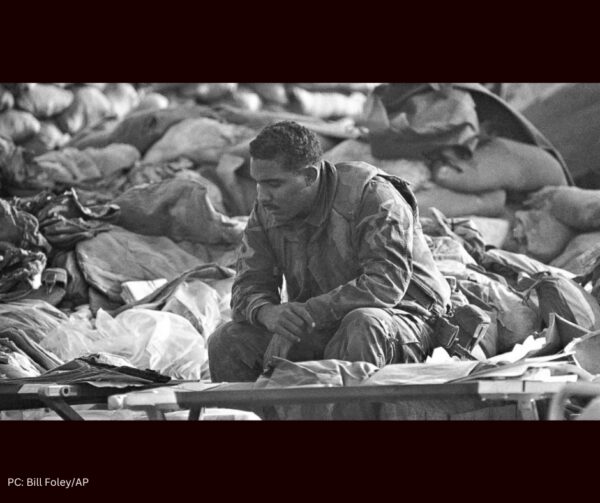

Beirut is with each of you — every day.

It’s there when you wake up, it is with you throughout the hours as you work, and it is there when you rest your head at the end of the day atop your pillow.

For the last year, I have been working with fellow author and military historian James Scott on a book about what happened in Beirut, one that will be published next fall in time for the 41st reunion.

We have gathered recently declassified records from the Marine Corps archives, Congress, the Pentagon, and the Reagan Presidential Library.

More importantly, we have spent hours upon hours talking, e-mailing, and texting with dozens of you. We have spoken with officers and enlisted men. From Colonel Geraghty to Private Henry Linkkila.

We have interviewed spouses and parents, to learn of the agony they, too, suffered in the days, weeks, and years that followed.

You have been so gracious as to provide us with more than a thousand pages of your personal letters, your diaries, and your photographs.

You have trusted us with your memories — and the memories of your loved ones — so that we can tell this story. Your story.

And we are honored.

It is our goal to remind America of what you endured.

It is also important to connect the dots — to remember that Beirut was not an anomaly, but the opening shot in a four-decade war that would see American troops battle in the mountains of Afghanistan and the streets of Iraq.

It is our duty to capture the lessons learned from the past and apply them going forward as wisdom. That is what we owe our sons and daughters, what we owe the next generation, so that they do not have to re-learn the same lessons in blood.

In the immediate aftermath of the BLT bombing, Marine Corps Commandant General Paul Kelley was called to testify before Congress. During a moment of frustration, as he grappled with myopic lawmakers unable to see the big picture, the general asked whether it would take a suicide bomber crashing an airplane for America to wake up to the reality of this new war.

How prophetic he was.

Each year since 1983, veterans, family, and friends have gathered here to remember our fallen heroes. The people in the city of Jacksonville and Marine Corps Base Camp Lejeune have been steadfast in their support.

And it is vital that this tradition continues, to remind America and the world that these men — these Marines, sailors, and soldiers — were a special breed. Trained as warriors, they went to Beirut on a mission of peace.

On the eve of the 40th anniversary of that horrible terrorist attack, we pause to remember those who died that Sunday morning.

But it is important that we remember they were not the only ones who gave their lives for this mission. During the two years, between 1982 and 1984, that American forces were deployed in Beirut, an additional 29 men were killed in the line of duty and hundreds more were wounded.

Just as the tragedy of Beirut remains with each and every one of you, it also haunted President Ronald Reagan. “Every day since the death of those boys,” he wrote in his memoir, “I have prayed for them and their loved ones.”

After he decided in March 1984 to end America’s involvement with the multinational force, Reagan sat down with a pen and paper and recorded his thoughts on Lebanon. His personal secretary later typed his notes and delivered them to White House speechwriters for possible inclusion in a future address, but the president’s private thoughts would never be uttered in public.

Until now.

Reagan’s notes, which we found amid his personal files, read like an anguished apology to you – to the men he had sent into harm’s way — men, he wrote, who had lived up to the finest traditions of the Marine Corps.

He wrote: “The goal we sought in that troubled place was worthy of their best and they gave their best. They were no part of our failure to achieve that goal. In the end, hatreds centuries old were too much for all of us,” Reagan concluded. “Yes, our Marines are coming home—but only because they did all that could be done. Semper Fi and God bless them.”

Thank you and God bless.